NanoRacks' proposed airlock paves way for a more commercial ISS

/In early February, NASA accepted a proposal from NanoRacks to send the first commercial airlock to the International Space Station in 2019. This milestone is only the latest of many that has seen the orbiting laboratory gain increased commercial use.

Houston-based NanoRacks has been sending small satellites to be deployed out of the Japanese Kibo airlock for seven years now. The airlock, however, is only big enough to send out things that are about the combined size of a small refrigerator. Additionally, the airlock is only opened about 10 times each year with only five of those allocated to NASA and commercial partners. The other five go to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, which owns the airlock.

A commercial solution

As such, NanoRacks has been working for over a year on a proposal to add a commercial airlock to the station. On Feb. 6, NanoRacks announced a partnership with Boeing to build the airlock, which would triple the number of CubeSats that can be deployed from the ISS during a single airlock cycle.

“The installation of NanoRacks’ commercial airlock will help us keep up with demand,” said Mark Mulqueen, Boeing’s International Space Station program manager, in a news release. “This is a big step in facilitating commercial business on the ISS.”

NanoRacks’ CEO Jeffrey Manber said he was pleased to have Boeing join in the development of the airlock.

“This is a huge step for NASA and the U.S. space program to leverage the commercial marketplace for low-Earth orbit, on [the] space station and beyond, and NanoRacks is proud to be taking the lead in this prestigious venture,” Manber said.

NASA also wants to increase commercial use of the outpost. It said the deployment of CubeSats and other small satellite payloads from the ISS has increased in recent years and it accepted NanoRacks’ proposal to support the demand.

“We want to utilize the space station to expose the commercial sector to new and novel uses of space, ultimately creating a new economy in low-Earth orbit for scientific research, technology development and human and cargo transportation,” said Sam Scimemi, director of the ISS Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “We hope this new airlock will allow a diverse community to experiment and develop opportunities in space for the commercial sector.”

NASA and NanoRacks said that in addition to deploying a large number of CubeSats in a single cycle, it can also use the airlock to transfer in or out larger items for installation or repair, something that is currently not possible with either the Kibo airlock or the crewed Quest airlock.

Payloads developed for the airlock will be coordinated through the non-profit Center for the Advancement of Science in Space, which manages the U.S. National Laboratory portion of the space station. According to NASA, all non-NASA funded payloads are subject to CASIS’ vetting process.

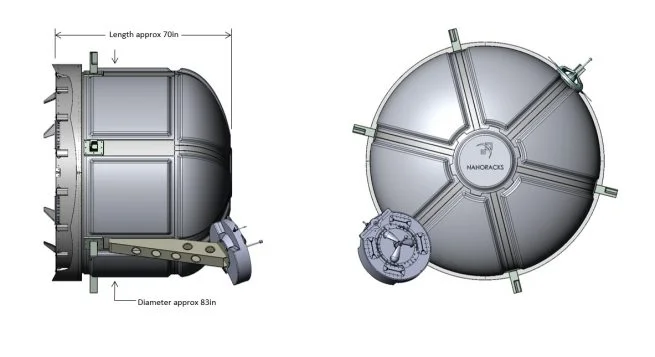

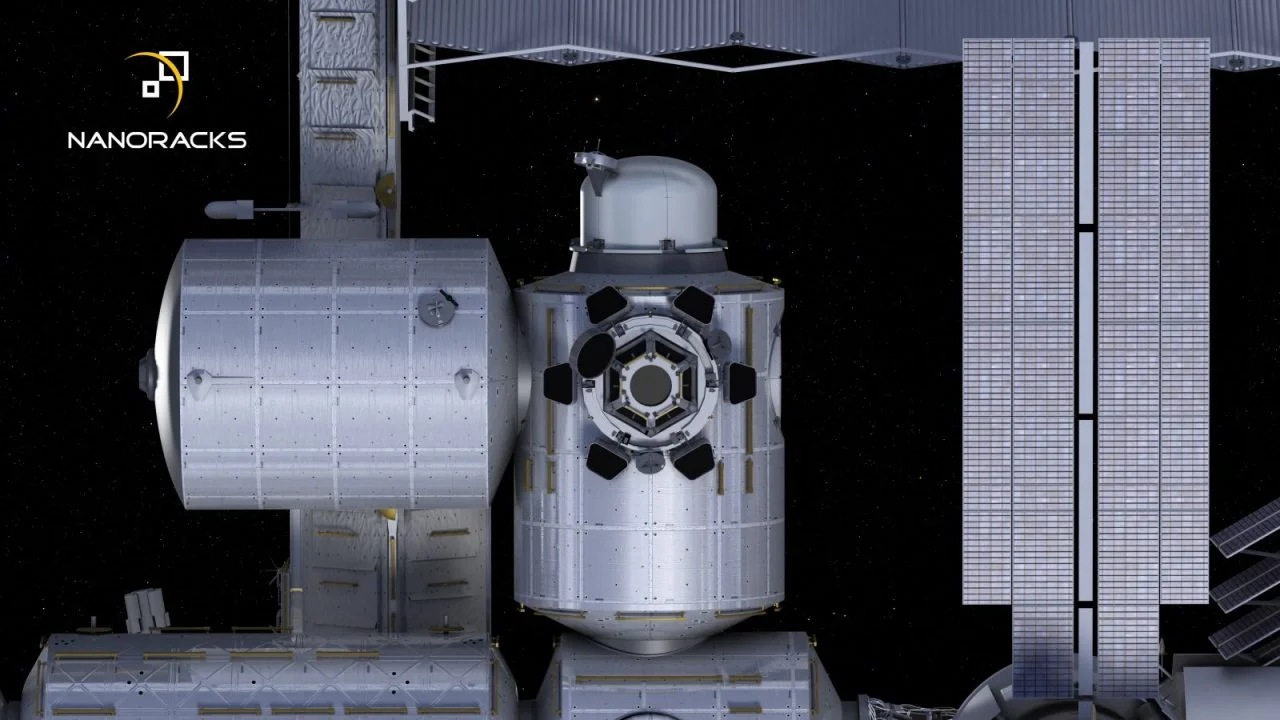

The airlock, which will be a dome-shaped structure about 2 meters wide and 1.8 meters long, will likely be launched in the trunk of a Dragon capsule. It will then be installed on the port side of the Tranquility module.

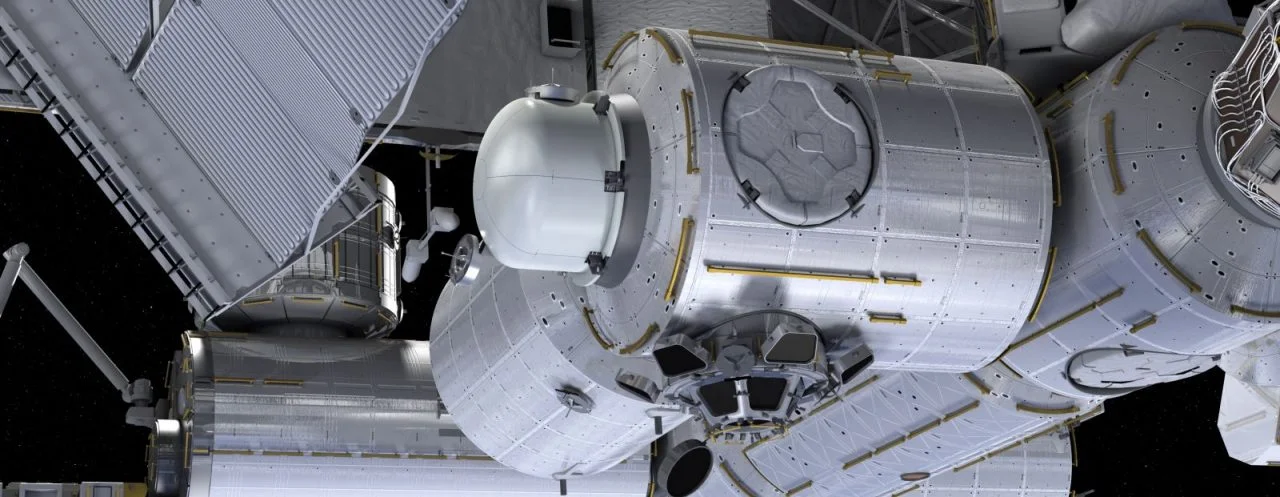

At present, NASA’s Pressurized Mating Adapter 3 is located there. Later this year, PMA-3 will be moved to the Space-facing port of the Harmony module to prepare it for commercial crew vehicles, something the space agency has already done with PMA-2 with the installation of IDA-2 in 2016.

Once attached to Tranquility, the airlock would be pressurized to allow the hatch to be opened. The inside could then be configured by the crew for a variety of tasks. Once ready for deployment, the hatch would be closed and the airlock depressurized.

The robotic Canadarm2 would then grab the airlock and move it to a deployment angle away from the outpost. After satellite deployment, the arm would then return the airlock to its port on Tranquility.

Ongoing movement toward commercialization

On the aft side of Tranquility is the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module. It and the commercial airlock are two examples of NASA’s ongoing efforts to both maximize the use of the space station and advance commercial space activity in low-Earth orbit.

Since 2006, NASA has been actively working to spur economic development on the ISS. The first notable example was the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services program. In May 2006, NASA selected six semifinalists for evaluation on sending cargo to the ISS via private companies.

COTS evolved into the Commercial Resupply Services program in 2013 after two finalists, SpaceX and Orbital Sciences (now Orbital ATK), successfully sent their spacecraft – Dragon and Cygnus, respectively – to the space station. Since then, regular cargo runs have been performed by those two companies.

In 2009, NanoRacks was founded by Manber, Mike Johnson, and Charles Miller to provide U.S. hardware for the U.S. National Lab. That same year, the company inked a deal with NASA to place its first lab on the outpost.

The next year, the company was the first to coordinate the deployment of CubeSats from the Kibo airlock using the Japanese Experiment Module Small Satellite Orbital Deployer. Since then, the company has sent up an external platform on the Exposed Facility on Kibo as well as their own small satellite deployer (brought up on the commercial Orb-1 Cygnus).

In 2010, building off the success of the commercial cargo program NASA started the Commercial Crew Development program to stimulate the development of privately operated spacecraft that the space agency could purchase seats aboard for flights to the ISS.

The program is currently in the Commercial Crew Transportation Capability phase. The two finalists are SpaceX and its Crew Dragon capsule, and Boeing with its CST-100 Starliner capsule.

While the program is running years behind schedule, the first crewed test flights are scheduled for 2018 with operational crew rotation flights in late 2018 or early 2019.

Commercialized ISS?

The point of all of NASA’s efforts to stimulate commercial activity in space is so it can focus on deep space exploration without the U.S. giving up its capabilities in low-Earth orbit. The next step in this process seems to be to help the development of commercial habitats.

BEAM, which was launched on behalf of Bigelow Aerospace by SpaceX in mid-2016, is the first human-rated expandable habitat. It has been deemed a success and NASA is now working with Bigelow on ways to utilize the small module.

According to Space News in October, NASA signaled its willingness to place a commercial module on the ISS. Two companies, Axion Space and Bigelow, said they were proceeding with the development of modules by 2020. This was in response to a NASA Request for Information.

Bigelow’s module would be an expandable module called B330. In 2016, the company announced it would have two modules ready for launch by 2020 with the potential for one of them to be attached to the ISS.

The other company, Axion Space, said it had completed a systems requirements review and would start a preliminary design review in December 2016.

Both companies hope to use the ISS as staging points for future stand-alone space stations.

Additionally, late in 2016, NASA signaled it was mulling the possibility of handing off control of the ISS to a commercial company by the mid-2020s, possibly before the current 2024 end-date for the space station.

“NASA’s trying to develop economic development in low-Earth orbit,” said Bill Hill, NASA Deputy Associate Administrator for Exploration Systems Development, in August. “Ultimately, our desire is to hand the space station over to either a commercial entity or some other commercial capability so that research can continue in low-Earth orbit.”

Whether that becomes a reality or not is still to be determined. NASA spends around $4 billion a year on space station operations and transportation, which is about 20 percent of the agency’s budget. Additionally, NASA is not the only owner of the space station. Four other space agencies work together to operate the outpost: Roscosmos, the European Space Agency, JAXA, and the Canadian Space Agency.

NOTE: While this article was written by Derek Richardson, it was originally published at SpaceFlight Insider. Feel free to head over there to read all the stuff they write about!