CRS-14 Dragon returns experiments, hardware to Earth

/Wrapping up a one-month stay at the International Space Station, SpaceX’s CRS-14 Dragon cargo ship returned to Earth with several thousand pounds of equipment for repair and experiments for further analysis.

Splashing down just after 3 p.m. EDT (19:00 GMT) May 5, 2018, just off the coast of Baja California in the Pacific Ocean, the capsule completed its second flight into space. Continuing with SpaceX’s goal of reusing hardware, this particular pressure vessel first flew to the ISS in April 2016 as part of the CRS-8 mission.

“Good splashdown of Dragon confirmed, completing SpaceX’s third resupply mission to and from the @Space_Station with a flight-proven spacecraft,” SpaceX tweeted.

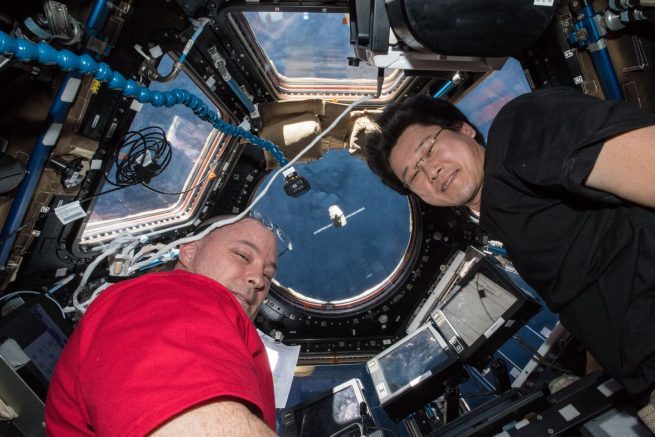

CRS-14 was launched atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on April 2, 2018. After a two-day trek to the outpost, Dragon positioned itself about 10 meters below the U.S. Destiny laboratory module. Then, using the robotic Canadarm2, the spacecraft was “captured” by Expedition 55 astronaut Norishige Kanai of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Over the next several hours it was moved to the Earth-facing port of the Harmony module where it was attached and remained for just over 30 days. During that time, the six-person crew gradually emptied the capsule of its 2,647 kilograms of experiments, supplies and consumables, before filling it with some 1,800 kilograms of equipment for an Earth return.

Among that downmass were several experiments, according to NASA. These include samples from the Metabolic Tracking study, which is designed to study techniques to improve pharmaceuticals in microgravity; the APEX-06 investigation, which grew grain crops so that scientists can understand the development of the seedling’s gene expression; and the third Fruit Fly Lab, which is studying the effects of microgravity and the space environment on innate immunity.

NASA said it was also returning Robonaut2, a humanoid robot that was launched in 2011 aboard Space Shuttle Discovery during STS-133. While it has been in space for more than seven years and was even given a set of “legs,” complications with its hardware never allowed it to fully operate as designed. In fact, it has remained packed away for most of its stay aboard the outpost with astronauts occasionally attempting repairs

This Dragon capsule was supposed to return to Earth several days ago on May 2. However, high seas in the recovery area forced SpaceX and NASA to postpone the unberthing operations to May 5.

In the early-morning hours of May 5, Dragon was remotely unberthed and moved to a position below the Destiny module in a procedure that essentially was a mirror of its arrival to the ISS a month ago.

At 9:23 a.m. EDT (13:23 GMT)—just minutes after NASA’s InSight lander was placed on a trajectory toward Mars from a mission launch from the West Coast—Dragon was released. At that time, the capsule and ISS were flying about 410 kilometers just south of Australia, according to NASA.

Over roughly 12 minutes, the spacecraft performed three departure burns to move Dragon safely away from the outpost’s 200-meter keep-out sphere. After that, it safely coasted away from the $100-billion, 400-metric-ton complex for about 5 hours.

While SpaceX has not confirmed official times, Dragon’s guidance, navigation and control bay door, which also houses the grapple fixture that the station’s arm hooks onto for capture, should have closed just before 1 p.m. EDT (17:00 GMT).

Sometime after 2 p.m. EDT (18:00 GMT), while above the Indian Ocean, Dragon’s Draco thrusters performed a 13-minute de-orbit burn, slowing the capsule down enough to intersect the thicker parts of the atmosphere, which would ultimately pull the vehicle back to Earth.

Before entry interface, however, Dragon had to shed its non-recoverable trunk, which houses batteries, solar panels as well as several pieces of unneeded ISS equipment. These burned up during re-entry, as planned.

Protected by a heat shield made of PICA-X, a variant of NASA’s Phenolic-Impregnated Carbon Ablator, the spacecraft survived temperatures that reached some 1,600 degrees Celsius as it made its way through the atmosphere.

Once it slowed down enough a series of parachutes deployed culminating in the release of three 35-meter diameter main parachutes to slow the vehicle down to just 115-25 kph. Splashdown took place some 640 kilometers southwest of Los Angeles.

SpaceX’s Dragon is currently the only vehicle that can bring large amounts of equipment “downhill” from the ISS. Once recovery teams remove the capsule from the ocean and place it on a ship, it will be transported to the Port of Los Angeles. There, high-priority cargo will be unloaded and shipped to NASA.

The remaining cargo will be removed and transferred to the NASA once Dragon is transported to the company’s rocket test facility in McGregor, Texas.

NOTE: While this article was written by Derek Richardson, it was originally published at SpaceFlight Insider. Feel free to head over there to read all the stuff they write about!