'New era in spaceflight': Crew Dragon docks with ISS

/For the first time since the end of the Space Shuttle program, a U.S. spacecraft designed to fly humans has docked with the International Space Station.

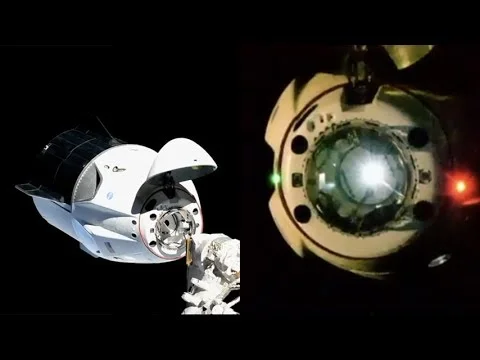

At 10:51 UTC March 3, SpaceX’s unpiloted Crew Dragon Demo-1 spacecraft made contact with the docking adapter at the forward end of the International Space Station. This came some 27 hours after launching atop a Falcon 9 from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A in Florida.

Following a “soft capture,” the docking ring on Crew Dragon was retracted, pulling the spacecraft the last several centimeters toward the ISS to make a firm link. It was the first SpaceX spacecraft to perform an autonomous docking as the first-generation cargo Dragon vehicles are designed to get close to the outpost for astronauts to use a robotic arm to “grab” and berth the spacecraft.

Over the next several hours, the space station’s Expedition 58 crew—NASA astronaut Anne McClain, Canadian Space Agency astronaut David Saint-Jacques and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko—worked to pressurize the small space between the spacecraft and station’s hatches before opening them to enter the vehicle for the first time. That hatch opening occurred at 13:07 UTC.

“Our sincere congratulations to all Earthlings who have enabled the opening of this next chapter in space exploration,” McClain said during a welcoming ceremony. “Congratulations to the teams at SpaceX and Boeing who have been working diligently to define what this new era of commercial spaceflight will look like.”

Following Crew Dragon’s March 2 launch, it worked to catch up and rendezvous with the outpost. Its first task once near the outpost was to reach “waypoint zero,” which is an area about 400 meters just below the ISS.

From there, the spacecraft was given the go ahead to move inside the 200-meter keep-out sphere to a position about 150 meters in front of the ISS—“waypoint 1.” Once there, several verifications were made, as this is a demonstration flight.

The first was to test the ISS crew’s ability to command Crew Dragon to retreat, in case an anomaly occurs. This command moved the spacecraft to about 180 meters before the crew initiated a hold, as planned.

After everything was verified as nominal, the spacecraft was then allowed to resume its approach to the docking port. This time, it made its way to “waypoint 2” about 20 meters in front of the station’s forward docking adapter.

Once there, it spend several minutes station keeping while engineers on the ground verified all systems were go for docking. Additionally, NASA’s Mission Control Center in Houston advised waiting until after orbital sunset before proceeding.

When the time finally came, Crew Dragon was commanded to move in for docking, successfully doing so while the ISS was orbiting some 400 kilometers north of New Zealand.

After the crew opened the hatches separating them from the interior of Crew Dragon, several things occurred.

The first was to ensure the air was OK for breathing. Saint-Jacques, McClain and Kononenko entered Crew Dragon wearing masks. This is typical for new vehicles and modules as air doesn’t move on its own in the microgravity environment of space. To ensure the air mixes properly, fans were turned on to circulate the interior atmosphere.

First inside was Saint-Jacques, followed by Kononenko. Once inside, the crew found Ripley, an anthropomorphic test device that will be used to gather data points on the human condition during flight.

Ripley, which was named after the main protagonist in the “Alien” film series, is wearing a SpaceX pressure suit, which astronauts flying aboard the spacecraft will wear during launch and re-entry.

Also inside Crew Dragon was a “zero-gravity indicator” plush Earth floating freely inside the cabin. Additionally, there was some 180 kilograms of cargo.

Dragon will remain docked to the ISS for about five days before being undocked and commanded to move away from the outpost.

Some five hours or so later it is expected to perform a 10-minute deorbit burn to fall back into the atmosphere and splash down in the Atlantic Ocean just off the coast of Florida.

Crew Dragon’s docking was the first to do so via the recently-added International Docking Adapter 2, which was itself brought to the ISS via a cargo Dragon spacecraft in 2016 and attached to Pressurized Mating Adapter 2 where Space Shuttles used to dock.

Following this mission, an in-flight abort test is planned for this same spacecraft and Ripley. Right now, NASA is targeting June 2019, however SpaceX CEO Elon Musk suggested this could occur in April.

After the test, and when NASA verifies the vehicle is ready to fly humans, astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken will board the Crew Dragon Demo-2 spacecraft to fly to the ISS on a flight profile similar to Demo-1. That is targeted for no-earlier-than July 2019.

“On behalf of Ripley, little Earth, myself and our crew, welcome to the Crew Dragon,” McClain said. “Congratulations to all of the teams who made yesterday’s launch and today’s docking a success. These amazing feats show us not how easy our mission is, but how capable we are at doing hard things. Welcome to the new era in spaceflight.”

NOTE: While this article was written by Derek Richardson, it was originally published at SpaceFlight Insider.