Final 1st-generation Japanese cargo ship leaves ISS

/After more than a decade of service, Japan’s final first-generation HTV cargo resupply spacecraft has departed the International Space Station, setting the stage for a new HTV-X vehicle capable of service in low Earth orbit and beyond.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s H-II Transfer Vehicle No. 9, also called Kounotori 9, was released by the 17.6-meter-long robotic Canadarm2 at 17:36 UTC Aug. 18, 2020. It’s set to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on Aug. 20.

“It’s been a real honor for the members of Expedition 63 ... to welcome HTV, conduct operations in it and now to be part of its departure — the ninth spaceship of the class,” said NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy, the current commander of the ISS, after Kounotori left the vicinity of the outpost. “Much congratulations to our colleagues and friends at JAXA.”

Kounotori 9 arrived at the ISS on May 25, 2020, having launched atop an H-2B rocket five days earlier from the Tanegashima Space Center, located on the island of Tanegashima some 40 kilometers south of kyushu. It rendezvoused with the ISS and was berthed to the Earth-facing port of the Harmony module using the Canadian robotic arm.

It brought to the outpost approximately 6,200 kilograms of cargo, including the final set of lithium-ion batteries to complete the bulk of the work to upgrade the space station’s power supply, which is perhaps the greatest legacy the kounotori (Japanese for “white stork”) spacecraft will leave behind at the ISS.

The upgrade work began with the launch of six lithium-ion batteries on Kounotori 6 in December 2016 and culminated with Kounotori 9.

In total, 24 new batteries were brought to the ISS over four HTV flights to replace 48 nickel-hydrogen batteries. These newer units are expected to be utilized for the duration of the space station program, which is currently slated to end sometime between 2024 and 2028.

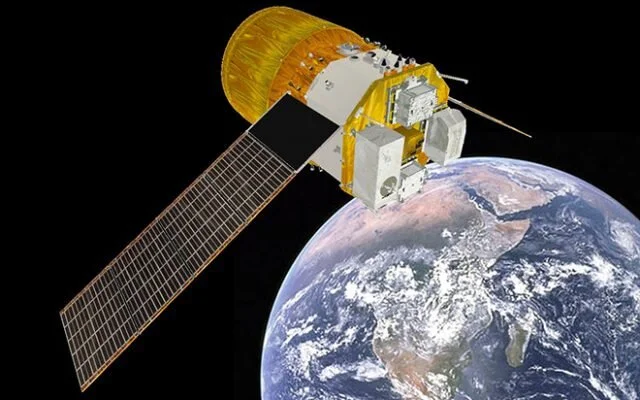

The HTV spacecraft is about 9.8 meters long and 4.4 meters wide with a dry mass of about 10,500 kilograms. It can hold up to about 6,200 kilograms of cargo.

It comprises four sections, a pressurized logistics carrier, and unpressurized logistics carrier, an avionics module and a propulsion module.

At the front of this section is a common berthing mechanism, which allows the vehicle to be attached to the ISS. Inside are eight payload rack bays arranged in two groups of four. The forward four are near the hatch while the other four are in the back of the pressurized section.

The unpressurized section holds an Exposed Pallet, which carries external experiments or orbital replacement units, such as the lithium-ion batteries.

This section also has a power and data grapple fixture so that the Canadian robotic arm can grab onto it and berth it to the outpost, or release it from the station at the end of its mission.

The avionics module contains the computers, batteries, guidance and other electrical subsystems while the propulsion module contains the fuel and main thrusters for the spacecraft.

The first HTV cargo ship, Kounotori 1, launched in September 2009 and remained at the outpost for 43 days. Kounotori 9 was berthed the longest at just over 84 days.

In total, the nine HTV spacecraft delivered nearly 45 metric tons of food, supplies and equipment to the ISS over its 11-year service.

A new-generation HTV is slated to be ready for launch by 2022. Called HTV-X, this vehicle will launch atop a new H-3 rocket, also from Tanegashima Space Center.

HTV-X is expected to feature a reusable pressurized cargo section in addition to sporting a lighter design in order to carry more cargo.

According to JAXA, the spacecraft is expected to have a docking adapter, rather than a berthing port. Therefore it’ll connect to the space station via one of the outpost’s two international docking adapters.

Moreover, HTV-X is also a potential resupply spacecraft for NASA’s planned Lunar Gateway, which is part of the U.S. space agency’s Artemis Moon program.

Japan has expressed interest in joining the United States on the Artemis program. Formal agreements have yet to be worked out, however, a Joint Exploration Declaration of Intent, or JEDI, has been signed as of July 2020.

Japanese astronaut Norishige Kanai, who served as the capsule communicator in Houston during the Kounotori 9 departure said the vehicle's departure is the beginning of a new chapter for JAXA as it sets the stage for the HTV-X in the next couple years.

“We’ve upgraded the capability of the new vehicle,” Kanai said. “We will expand our activity in space, not only on ISS, but beyond low Earth orbit. We look forward to seeing HTV-X in the near future. Until then, farewell HTV. Arigato. Sayonara Kounotori.”

NOTE: While this article was written by Derek Richardson, it was originally published at SpaceFlight Insider.